Is Art Essential?

by Roger Manley

As I write this, weeks have passed since our governor mandated closing all non-essential institutions statewide, to keep the pandemic down to a more manageable, if not ignorable, level. As one of those institutions deemed non-essential, the Gregg cancelled all its programs and closed its doors to visitors, though the staff continues to work from home and will do so as long as necessary.

Art is the highest form of hope. —Gerhard Richter

Meanwhile, the change in perspective brought about by the change of work locations, along with the wording of that announcement, prompted me to ponder, is art essential? I think so. Two past experiences convince me we can’t do without it.

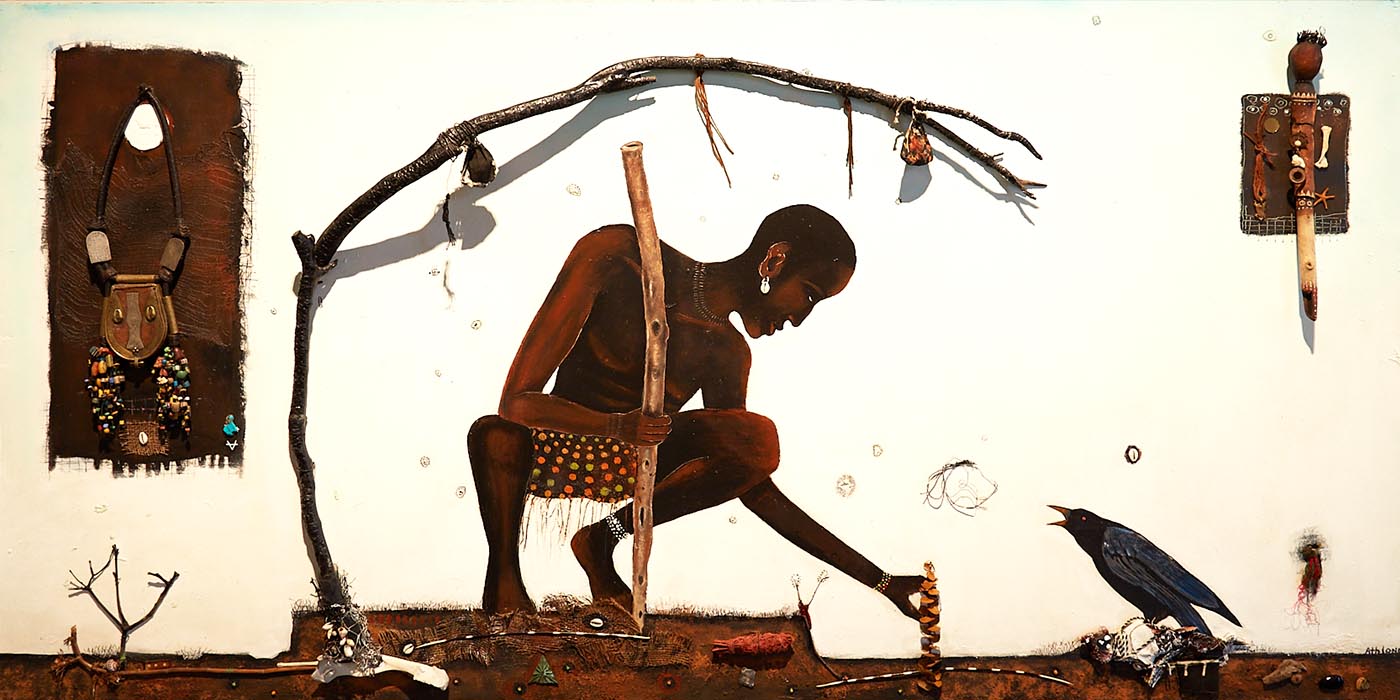

Back in the mid-1970s, due to a series of events too roundabout to go into here, I found myself living with an isolated group of Aboriginals in Australia’s central desert. For the better part of an often lonely year, I did not see or speak with another non-native person. A big part of every day there was devoted to “caloric survival”—hunting lizards, birds, and small mammals, digging for grubs and honey ants, collecting roots and nuts, winnowing and grinding seeds—but an equal amount of time was occupied with “spiritual survival” activities that included things like creating vast ground-paintings, erecting long rows of carved poles tied with human hair string, and making “costumes” of chopped feathers glued on with human blood. Entire days were spent gathering materials, painting each other’s bodies, sweeping sand into decorated mounds, and drawing intricate spiraling lines and radiating circles on the ground, while groups of singers chanted to the percussive accompaniment of clacking boomerangs or the low thumping of beating the ground with sticks.

I was the only “audience,” and none of this was done for my entertainment. At first, I often found myself mystified and somewhat disappointed when, after long hours of preparation, what I took to be the “ceremony itself” seemed so brief. After days spent getting ready, there would be a quiet lull while everyone rested and then, on signal, a few frantic minutes of frenzied stomping and shouting during which the ground paintings would be obliterated and most of the feathers and plant materials covering the “performers” would flake off and blow away into the desert.

In time, I began to realize that all of it—the gathering, the preparation, and the “performance”—was all one big, ongoing spiritual activity that included the hunting and gathering of food as well. The scattered feathers and dried flakes of blood breaking off and blowing away weren’t the annihilation of the artworks but their distribution. They were seen as seeds for more game to be hunted and plants to be gathered. It also became clear that if people who lived in one of the world’s harshest and least forgiving environments would devote as much time to making art as to finding food, they must have viewed it as essential.

The second experience, which cemented the “essentialness” of art for me, was a museum exhibition I encountered not too long after I returned from Australia.

It was a show on the art of the Warsaw Jews. Poland once had the largest and most important population of Jews in the world, with artists, artisans, merchants, scientists, and scholars who had developed a vibrant society that thrived for more than a thousand years. The first rooms of the exhibition celebrated its achievements in cases filled with stunning objects—golden Torah crowns and ornate silver pointers, gleaming menorahs and gorgeous Kiddush goblets with elaborately repousséd decorations, fine brass scientific instruments and inscribed scrolls with richly illuminated calligraphy, all of it a glittering feast for the eye.

In the final room, though, the chronology reached the more recent past. Here cases held objects discovered in the death camps of the Holocaust as the Second World War came to an end. These were the same kinds of things that had seemed so dazzling in the earlier cases, but miniature versions made with whatever could be scrounged by the prisoners: little menorahs and Torah pointers made from scraps of silvered paper torn from discarded cigarette wrappers, crowns and Shabbat candlesticks fashioned from pieces salvaged from tin cans, bits of paper with calligraphy inked in with rust and water. Everything was diminutive because it had to hidden, but also because in the camps even foil and tin were as hard to obtain as precious metals once had been.

If the earlier object had seemed impressive, these were overwhelming. Despite knowing they would soon be exterminated, the doomed makers had nevertheless felt it crucial to continue making art as much as the terrible circumstances would allow. They knew that to quit would be to surrender their humanity. If that’s not a definition of essential, I don’t know what is. They had understood that as much as anything else we do, the arts are what make us fully human.

Now, with the economy impacted by the pandemic and talk of budget cuts and program cancellations in the months and years ahead, I hope our lawmakers and administrators will somehow come to a similar realization. Even at a STEM-oriented campus like NC State, students need art and opportunities to see and participate in it in order to emerge from their years in school with an understanding of what it means to lead a worthwhile life.

Nuclear physicist Robert R. Wilson famously expressed this when he found himself having to explain the reasons for building a particle accelerator to a U.S. senator who questioned its value in the Cold War. In slightly shortened form:

Senator: Is there anything […] that in any way involves the security of the country? […]

Wilson: Nothing at all.

Senator: It has no value in that respect?

Wilson: It only has to do with the respect with which we regard one another, the dignity of men, our love of culture. It has to do with those things. It has nothing to do with the military. […]

Senator: Is there anything here that projects us in a position of being competitive with the Russians, with regard to this [nuclear arms] race?

Wilson: Only from a long-range point of view, of a developing technology. Otherwise, it has to do with: Are we good painters, good sculptors, great poets? I mean: all the things that we really venerate and honor in our country and are patriotic about. In that sense, this new knowledge has all to do with honor and country, but it has nothing to do directly with defending our country, except to help make it worth defending.

Wilson understood that the arts and sciences, like belief and survival, are aspects of the same whole. An artist as well as scientist, he expressed this concept best in a graceful stainless steel sculpture that he made and installed at Fermilab, outside Chicago, named the Mobius Strip. As any sixth grade math student knows, its two sides are really one continuous surface.

–Roger Manley, Director of the Gregg Museum of Art & Design

- Categories: